What They Don't Teach in Most Business Schools: Leadership and Success Criteria.

More than a decade ago I gave a speech and referenced the book, What They Don't Teach You at the Harvard Business School. Having worked in several universities and having dealt with the business schools and programs in those schools, I tend to be a bit more hesitant with my claims than was Philip Delves Broughton and his publisher with their title. And, even though I never attended a business school, I've worked in, ran, and consulted to businesses all my life, so I'm claiming the right to reflect on some aspects of those experiences and the resulting learning.

Are the Criteria for Leadership Success Rational?

In this case, by rational I mean that the premises and conclusion in my deductive model match another's conclusion that I hear or read.

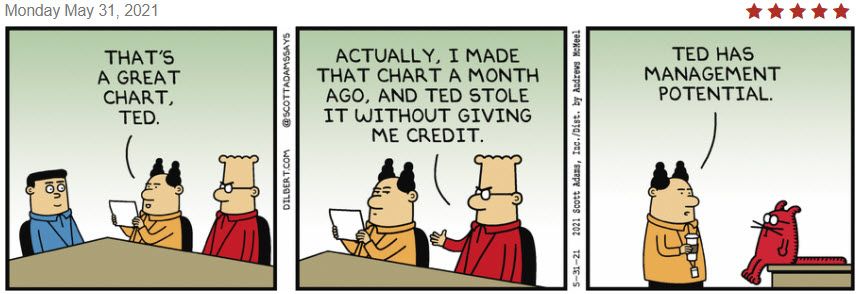

Here's today's offering from Scott Adams:

Dilbert is doomed or done in by the Pointy-Haired Boss's premises about management potential. Somehow where the PHB ended up is not what I think I would have concluded.

How often have you seen that happen? In hiring and in promotions?

Once when working with the practice group in a law firm, we were discussing the topic of how to select the best attorney's when adding to the firm. I recall one senior lawyer in the group saying: "My biggest limitation is that I keep looking for people like me and that's probably not the best strategy."

How true. Just as "what got you here may not get you there", hiring someone like you already have may not be the best strategy for the organization, business, or the firm. What criteria are the candidate evaluators really using when doing interviews or screening paper?

The same applies to promotions. Existing people in power may well judge the talent who work for them on the basis of the extent to which they match the criteria the boss thinks are important which may also be the criteria the boss applies to him- or herself.

It that's the best strategy for the organization or the business, great!

Often, however, it isn't and performance suffers as a result.

So What?

What do you do about situations in which the conclusion doesn't match yours?

We often start by arguing that the conclusion is wrong. With lots of people, that's the "wrong" place to start. Instead, we want to know the premises that underly their conclusion. That's the gold we want to mine in order to figure out how the individual got to this conclusion (that we conclude is erroneous).

If you pursue the issue may depend upon your position in the organization. If you are a peer or superior, it is very different than if you are a subordinate. Often, subordinates will "let it pass". That is, they will accept a conclusion and move on even when it impacts them directly and is clearly perceived as wrong.

Often, peers who witness the same process will not say anything. Why? It could be that they "don't want to get involved". That's the same issue law enforcement faces when trying to get people who may have witnessed a crime to step forward. They may also not want to set themselves up for the same kind of scrutiny. Neither of which seems like a particularly good reason not to speak up, but it serves as one nonetheless.

Looking in the Mirror

We often only hold our own mirror. When I do that I'm reminded of a major meta-study entitled "Flawed Self Assessment". It covers research and gives implications for health, education, and the workplace.

It seems that we're not particularly good at giving ourselves accurate self-assessments. If, at the same time, we're not particularly motivated to get input from others, then the state of being tends to be locked in place.

If that's the case for a lot of people, then the only way in might be with questions. With questions, we don't challenge the conclusion, we're simply exploring the premises.

- What leads you to conclude that?

- What experience have you had that drives this conclusion?

- If I were evaluating your recommendation, what's the upside?

- What's the potential downside?

- Etc.?

We don't change minds with questions, but might "soften the barrier" that tends to resist influence. If the individual asking is a subordinate, it is the least risky way of getting more insight so that you can decide the best strategy forward.

And like so many things of this nature . . . nothing is easy.